File image of Keir Starmer. Source and credit: Simon Dawson / No 10 Downing Street.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer is taking credit for a series of Bank of England rate cuts, which risks compromising monetary policy independence.

The Bank of England was set free from the Government by Gordon Brown in 1998, but 27 years later and his Labour Party successors are compromising that independence.

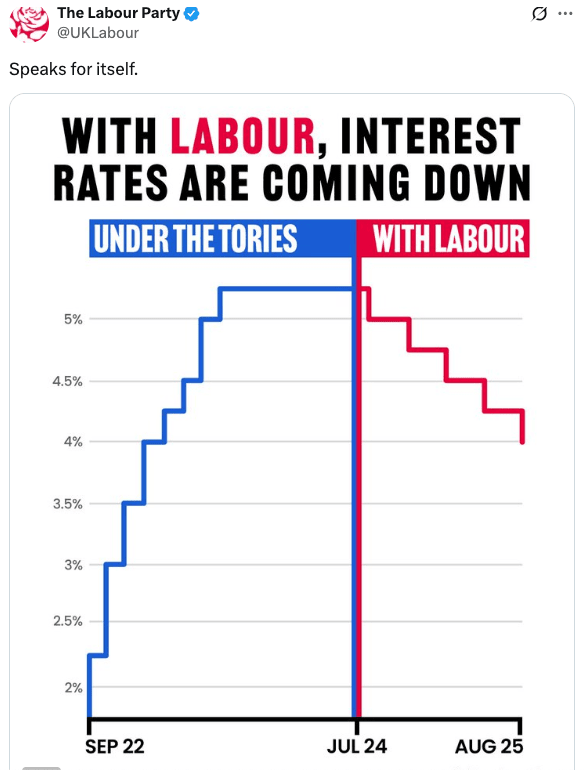

Following Thursday's 25 basis point interest rate cut, the Prime Minister, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Labour parliamentarians ran a series of coordinated social media posts taking credit for the 25 basis point reduction in interest rates.

"Good news: interest rates have been cut five times since we came into government. Homebuyers are £1000 better off on their mortgages than they were a year ago. That's our Plan for Change in action," said Prime Minister Keir Starmer following the decision.

"Since the General Election, interest rates have been cut five times and are now at their lowest level for two years - bringing down the cost of mortgages and loans across the UK. By bringing stability back to the country's finances we're putting more money in people's pockets," said Chancellor Rachel Reeves.

A study of their social media posts and press appearances reveals the messaging is not new and that the administration has been steadily tying Bank of England policy decisions to government policy.

This marks a departure from previous governments - both Labour and Conservative - that avoided regular commentary on Bank of England policy making, let alone taking credit for any policy moves.

The developments in the UK are contextualised by U.S. President Donald Trump's more overt attempts to influence the Federal Reserve, which have raised risk premiums on U.S. assets in 2025, contributing to the decline in the Dollar.

The Pound faces similar risks from Starmer and Reeves' attempts to convince the public that government and central bank policy are aligned and coordinated.

Image shows official Labour Party messaging following Thursday's interest rate decision.

Investors are intrinsically more trustful of institutions that are deemed to be independent of politics, judging that technocrats are better decision makers than politicians who operate in short-term, four-year cycles.

For Pound Sterling, any building risk premium associated with questions of central bank credibility would therefore prove costly.

There is a growing risk that future interest rate decisions are compromised by political associations. We might already be seeing this: economists and financial market commentators are questioning why the Bank's governor, Andrew Bailey, went against his Chief Economist and Deputy Governor for Monetary Policy by voting for a cut.

The two professional economists on the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) saw a cut as being too risky given that inflation is rising, and could soon reach 4.0%, which is double the Bank's target.

"Confused about what’s going on at the Bank of England? You should be. Higher inflation normally requires high or increasing interest rates. But now, higher inflation means lower interest rates. No surprise that 4 of 9 MPC members voted against this policy move. What a muddle!" says Andrew Sentance, an economist who formerly served on the MPC.

"Bailey has already been caught out loosening policy too much when inflation is rising - back in 2nd half of 2021 and early 2022. He is making the same mistake again, when his Deputy Gov for Monetary Policy and Chief Economist are urging a more cautious policy," he adds.

There's a risk that consumers and businesses perceive Bank of England policy as being politically motivated, undermining the perception that it is a credible stalwart in fighting inflation.

A belief that there is no longer a controller of inflation would encourage workers to press for higher wages and businesses to raise prices, which would add momentum to the inflationary cycle.

Reeves and Starmer's attempt to draw an association with the central bank rests with the populist undertones that come with lowering interest rates: it's stimulatory and is intended to boost the economy and jobs.

But a truly independent central bank would realise that making unpopular decisions is entirely within its remit: rising unemployment is sometimes a necessary trade-off central banks must make in order to control inflation. They're not here to be popular, they're here to deliver for the greater good, and nothing compromises the greater good more than inflation does.